Chapter 19 Git and Github

19 Learning Objectives

- Explain which initialization and configuration steps are required once per machine, and which are required once per repository.

- Go through the modify-add-commit cycle for single and multiple files and explain where information is stored at each stage.

- Configure Git to ignore specific files, and explain why it is sometimes useful to do so.

- Explain collaboration options on GitHub

- Go through the fork & pull workflow

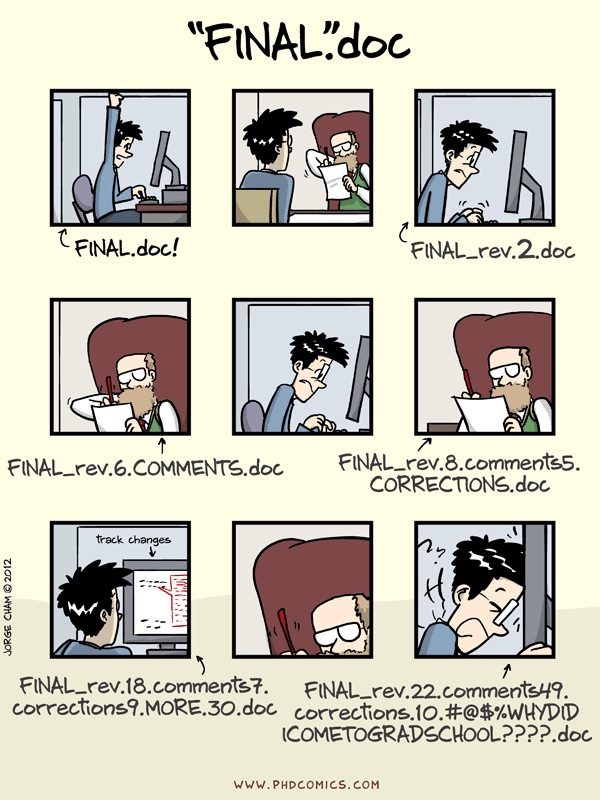

We'll start by exploring how version control can be used to keep track of what one person did and when. Even if you aren't collaborating with other people, version control is much better for this than this:

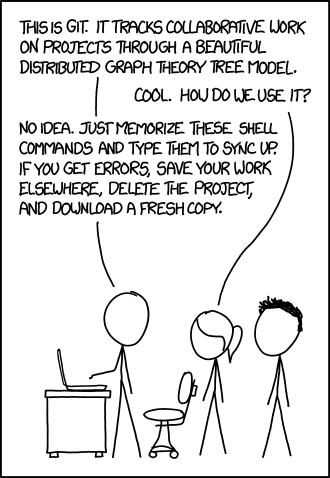

Git is powerful and complicated. We can do a full day workshop on git alone. But it is also quite possible to harness it's powers by cycing through three commands: add, commit, push. So even if you don't understand what's going on underneath the hood, knowing just these three commands can get you very far.

xkcd

19.1 Starting with Git

The first time we use Git on a new machine, we need to configure a few things.

Here's how Dracula sets up his new laptop:

$ git config --global user.name "Vlad Dracula"

$ git config --global user.email "vlad@tran.sylvan.ia"(Please use your own name and email address instead of Dracula's, and please use the same email as you used to make your GitHub account.)

Git commands are written git verb, where verb is what we actually want it to do. In this case, we're telling Git to configure our name and email address,

The two commands above only need to be run once: the flag --global tells Git to use the settings for every project on this machine.

19.1.1 Creating a repository

Once Git is configured, we can start using it to share code on GitHub.

Follow these instructions to create a new GitHub repository. Be sure to add these options:

- Call the repo "plsc31101-final-project"

- Create a README.md file

- Create a .gitignore file

- Don't add a license for now. Later, you can add a license for your project (see here for information on which license to choose.)

Git without GitHub

Git is often used in conjunction with GitHub. But you can also use git to track changes locally on your computer.

If you wanted to start using Git from scratch on a new project, you can create a directory and tell Git to make it a repository -- a place where Git can store old versions of our files -- using the command

git init$ git init

After you create your directory, clone a local copy onto your computer by following these instructions. Be sure to clone in a location that you will remember!

$ cd ~

$ git clone https://github.com/vlad/plsc31101-final-project.gitNow, navigate into your new git repository

$ cd ~/plsc31101-final-projectIf we use ls -a to show the directory's contents, we can see a hidden directory called .git:

$ ls -a

# . .gitignore

# .. README.md

# .git Git stores information about the project in this special sub-directory. If we ever delete it, we will lose the project's history.

We can check that everything is set up correctly by asking Git to tell us the status of our project:

$ git status19.1.2 git add: tracks files

Let's add a file into our directory.

$ touch file.txtNow, when we type in git status, we see something like this:

$ git status

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

# The "untracked files" message means that there's a file in the directory that Git isn't keeping track of. We can tell Git that it should do so using git add:

To add new files, you can either type git add [file name] like so:

$ git add file.txtOR, if you want to add ALL the new files in a repository, you can use the . shortcut:

$ git add .Now if we use git status we should no longer see any untracked files.

19.1.3 git commit: saves files

Git now knows that it's supposed to keep track of all the files in your repo,but it hasn't yet recorded any changes you've made to those files. To get it to do that, we need to run one more command:

$ git commit -am "First Commit"

# [master (root-commit) f22b25e] First Commit

# 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

# create mode 100644 ...When we run git commit, Git takes everything we have told it to save by using git add and stores a copy permanently inside the special .git directory. This permanent copy is called a revision and its short identifier is f22b25e. (Your revision may have another identifier.)

We use the -a flag (for 'all') to tell Git that we want to commit all the changes we've made to every file. If we just run the git commit without the -a option, Git will expect us to specify which file's changes we want saved.

We use the -m flag (for "message") to record a comment that will help us remember later on what we did and why. If we just run git commit without the -m option, Git will launch nano (or whatever other editor we configured at the start) so that we can write a longer message.

If we run git status now:

$ git status

# On branch master

# nothing to commit, working directory cleanit tells us everything is up to date.

If we want to know what we've done recently, we can ask Git to show us the project's history using git log:

$ git log

# commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

# Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

# Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

# First commitgit log lists all revisions made to a repository in reverse chronological order. The listing for each revision includes the revision's full identifier (which starts with the same characters as the short identifier printed by the git commit command earlier), the revision's author, when it was created, and the log message Git was given when the revision was created.

19.1.4 git push: moves changes from one branch to another.

Systems like git allow us to move work between any two repositories. In practice, it's easiest to use one copy as a central hub, and to keep it on the web rather than on someone's laptop.

This is where GitHub comes in: it holds the master copy of a repository, and allows us to move changes between multiple local copies.

To copy our changes from our laptop to our GitHub repo, we can use git push:

$ git push origin master

# Counting objects: 9, done.

# Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

# Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done.

# Writing objects: 100% (9/9), 821 bytes, done.

# Total 9 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

# To https://github.com/vlad/plsc31101-final-project

# * [new branch] master -> master

# Branch master set up to track remote branch master from origin.This tells git to push our changes to the repository's "origin" -- i.e., the copy on GitHub.

Now open up a web browser and navigate to your GitHub repository. What do you see?

19.1.5 Challenge 1

Navigate to https://github.com/plsc-31101/replication-template and clone the repository to your computer.

Copy all the files and directories in this folder into your new github repo (plsc31101-final-project).

Then add, commit, and push. Use this template for your final project!

Cheat sheet

$ git add .

$ git commit -am "commit message"

$ git push origin/master19.1.6 Ignoring Things

Oftentimes we'll have files that we do not want git to track for us. These include sensitive data files, as well as hidden files with extensions like .Rhistory, .ipynb_checkpoints, and .DS_Store (Dropbox).

Let's create a few dummy files:

$ touch a.dat b.dat data/c.csv data/d.csvand see what Git says:

$ git status

# On branch master

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

#

# a.dat

# b.dat

# data/

# nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)Putting these files under version control would be a waste of disk space. What's worse, having them all listed could distract us from changes that actually matter, so let's tell Git to ignore them.

We do this by creating a file in the root directory of our project called .gitignore.

$ nano .gitignore

$ cat .gitignore

*.dat

data/These patterns tell Git to ignore any file whose name ends in .dat and everything in the data directory. (If any of these files were already being tracked, Git would continue to track them.)

Once we have created this file, the output of git status is much cleaner:

$ git status

# On branch master

# Untracked files:

# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

#

# .gitignore

# nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)The only thing Git notices now is the recently-changed .gitignore file. You might think we wouldn't want to track it, but everyone we're sharing our repository with will probably want to ignore the same things that we're ignoring. Let's add and commit .gitignore:

$ git commit -m "Add the ignore file"

$ git status

# On branch master

# nothing to commit, working directory cleanAs a bonus, using .gitignore helps us avoid accidentally adding files to the repository that we don't want.

$ git add a.dat

# The following paths are ignored by one of your .gitignore files:

# a.dat

# Use -f if you really want to add them.

# fatal: no files added If we really want to override our ignore settings, we can use git add -f to force Git to add something. We can also always see the status of ignored files if we want:

$ git status --ignored

# On branch master

# Ignored files:

# (use "git add -f <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

#

# a.dat

# b.dat

# c.dat

# results/

# nothing to commit, working directory clean19.1.7 Challenge 2

Continue editing the .gitignore file to add extentions you don't want to track, like .DS_Store, .Rhistory, etc.

19.1.8 Pulling / Syncing

Oftentimes we need to sync our local repo with the master branch (the default branch) on GitHub. For instance, let's say you have two computers, one at home and one at work. We made a change using our work computer, and pushed it to the master branch on GitHub. But then we go home and find that our local copy is out of date.

A more common method of syncing branches is to use git fetch followed by git merge; or git pull.

git fetchfollowed bygit mergecombines your local changes with changes made by others.git pullis a convenient shortcut for completing bothgit fetchandgit mergein the same command

$ git pull origin/masterThis is helpful if you want to merge your changes and the master branch.

Commit before your pull

Because

pullperforms a merge on the retrieved changes, you should ensure that your local work is committed before running the pull command. If you run into a merge conflict you cannot resolve, or if you decide to quit the merge, you can usegit merge --abortto take the branch back to where it was in before you pulled. See here for more info on fetching and merging.

Sometimes git pull will cause merge conflicts, meaning that your local repository and master branch diverged on some lines of code, and git doesn't know which version you want to keep.

If you know that you want to keep the master branch version, you can overwrite your local repository like this:

$ git fetch

$ git reset --hard origin/masterLet's break this down:

git fetchretrieves a record of all changes made in the master branch.git reset --hard origin/masterwill reset your local repo to match the master branch.

With these commands, every tracked file will be overwritten to match to its version in master. Be careful with this: all local changes will be lost.

19.2 Collaborating

Version control really comes into its own when we begin to collaborate with other people.

All of the course notes are contained in their own Github Repo: https://github.com/plsc-31101/course

I've created a directory in this repo called 98-Final-Projects. We're going to collaborate on this directory using git to collect information about your final projects.

There are two main ways to collaborate on github:

- Adding individual collaborators to a project

- The fork & pull model.

The first method adds users to your project, giving them full permissions to make changes. For this course, I added Pete Cuppernull as a collaborator, so that he could push commits easily to the repository without my expressed approval.

Collaborating in this fashion is very similar to the workflow described above.

19.2.1 Fork & Pull Model

GitHub also allows you to to accept individual contributions from users without granting them full access. This if referred to as the Fork & Pull model.

Fork & Pull involves the following steps:

1. Fork an existing repo

The first step in in this workflow is to fork an existing repository. A fork is a copy of a repository that you manage yourself. Forks let you make changes to a project without affecting the original repository.

To fork a repo:

- On GitHub, navigate to plsc-31101/course,

- In the top-right corner of the page, click Fork.

Now you have a fork of the original repo in your-user-name/course

2. Commit a change

We've already seen how you can commit a change directly in GitHub's web interface. But when working with code, you often want to develop your scripts on your computer, so you can test it using R, Python, etc.

To do this, you first need to clone your fork onto your computer.

- On GitHub, navigate to your fork of the

courserepository. - In the right sidebar of your fork's repository page, copy the clone URL for your fork.

- Use

git cloneto clone the repo.

$ cd ~

$ git clone https://github.com/YOUR-USERNAME/courseWe're now ready to make a change to the repo. Create a file in 98-Final-Projects directory named after yourself. Protip: the touch command quickly creates an empty file.

$ cd course

$ touch 98-Final-Projects/rochelle-terman.mdOpen up that file in a text editor (I like Sublime Text) and add:

- The title of your project (in a header 2)

- A 1-2 sentence description of the project

- A link to your github repo (that you just made)

Markdown Reminder

Files with the extension .md are called markdown files. Markdown is a markup language used to convert plain text to HTML and many other formats. It's basically a way to add markup to a text (making things bold, lists, links, etc) using very simple syntax. It is often used in README files in software packages. You may have also noticed that all of the lessons for this course are written in markdown, as is many of the text files on GitHub. You can learn more about how to write GitHub-flavored markdown here.

Then add, commit, and push the change.

$ git status

$ git add 16_final-projects/rochelle-terman.md

$ git commit -am "my final project info"

$ git push3. Submit a pull request

Navigate to your GitHub repo (online) and check out your change!

Remember when you forked the repository originally? That means that your repository is different from mine, and from everybody elses. What if you want to share your change with others?

To do this, navigate to your GitHub repository and click the green icon to submit a pull request.

After you submit, I have the option to accept.

4. Keep your fork synced

It's good practice to keep your fork synced with the upstream (i.e. the original) repository. That way, if I make a change to PS239T, you can easily pull that change into your fork.

You can configure Git to pull changes from the original, or upstream, repository into the local clone of your fork.

$ git remote -v

$ git remote add upstream https://github.com/plsc-31101/course.git

$ git remove -vWith git remote -v, you'll see the current configured remote repository for your fork.

Now you can sync your fork with the upsteam repo using git fetch:

$ git fetch upstream

$ git merge upstream/masterTo learn more:

- [GitHub documentation](https://help.github.com

- This great stackoverflow answer